Eating fat makes you fat. Eating the fat that causes heart disease fills your body with that fat. Fat is bad. Some kinds of fat are especially bad. Avoid all of it.The theory, in part and simply put, was that you are what you eat. If you eat fat will be fat.

Although this is clearly wrong on the surface, there is a deeper truth to it - we ARE what we eat. EVERY cell in the human body is lipid-based, i.e., made of fat, and this is especially true in the brain.

Sports nutritionist Dr. John Berardi (Precision Nutrition) has long been an advocate of splitting fat intake equally between saturated fats (coconut oil, butter), monounsaturated fats (nuts, avocados, and olive oil), and polyunsaturated fats (fish, seeds, and nuts).

Below this post from Nautilus, I am also including an excellent "explainer" by Ryan Andrews of Precision Nutrition on healthy and unhealthy fats.

How The Big Wrong Fat Message Got So Widely Accepted

Posted By Amos Zeeberg on May 30, 2014

Nutritional advice about eggs, naturally high in cholesterol, has been scrambled

over the past 50 years. Jag_cz via Shutterstock

The practice of nutritional science faces some significant problems, and they are mainly of its own making. For decades, starting in the 1950s, a consensus of experts recommended that Americans cut down on fat, cholesterol, and saturated fat so as to minimize their risk of heart disease.

In more recent decades, the consensus has, like an ocean liner, slowly changed direction and even reversed course. First, the warnings about fat diminished and then disappeared—the problem wasn’t fat but certain problematic fats, the exact identity of which were also in flux. Then the firm limits on cholesterol were lifted—dietary cholesterol didn’t significantly change blood cholesterol in most people, and the total blood cholesterol wasn’t a very important factor in heart disease, anyway.

Over the past few years, studies of people’s actual health outcomes, not just biomarkers with indirect connections to health, suggest that saturated fat isn’t so bad either. As the expert bodies slowly internalize these results, the public sees a confusing contrast: Researchers seem to be coalescing around the idea that saturated fat isn’t the enemy, while public-health agencies continue to demonize it. This no doubt breeds some degree of deserved skepticism about the science behind our nutritional guidelines.

How did it get to be this way? How is the nutritional science advanced by public-health experts in such stark contrast with new science research?

Gary Taubes, one of the most influential critics of the “diet-heart hypothesis,” lays most of the blame on Ancel Keys, a physiologist at the University of Minnesota. Taubes says Keys based the theory on a tiny bit of research and forcefully, effectively promoted it to scientists. Other skeptics of the hypothesis have also pinned the error on Keys.

But I wonder if there’s another factor that helped propel the diet-heart hypothesis to become conventional wisdom despite a dearth of solid evidence, namely the old idea that “you are what you eat.” It makes a certain kind of obvious sense that eating fat will make you fat. What’s more, eating fat will provide more fuel for the plaques, made of fat, that were known to cause heart attacks on strokes. And of course it makes sense that eating cholesterol, a kind of fatty molecule, will increase cholesterol, a fat associated with heart disease, in your blood.

This idea was supported by Keys’ research and, more importantly, it made a clear, easily graspable lesson to push to the public. Eating fat makes you fat. Eating the fat that causes heart disease fills your body with that fat. Fat is bad. Some kinds of fat are especially bad. Avoid all of it.

But it turned out that you are not, in fact, exactly what you eat. Biology is more complicated than that.

~ Amos Zeeberg is Nautilus’ digital editor.

* * * * * * * * * *

Ryan Andrews is a former competitive bodybuilding, holds a MA in exercise physiology and an MS in nutrition, and is a Precision Nutrition coach and writes a great many of the informative articles post at the site. He also has adopted a plant-based diet while adhering to the macro-nutrient of the PN approach to nutrition.

All About Healthy Fats

By Ryan Andrews

Fats are organic molecules made up of carbon and hydrogen elements joined together in long chains called hydrocarbons. These molecules can be constructed in different ways, which creates different types of fat and their unique properties. The molecular configuration also determines whether fats will be healthy or unhealthy.

Fat types

There are 3 main types of dietary fat: saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated.

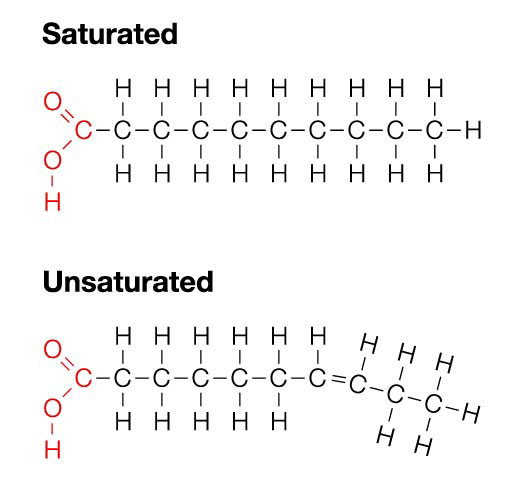

The difference between saturated and unsaturated fats lies in the bond structure. (See the diagram below.)

Saturated Monounsaturated Polyunsaturated Omega-3 Omega-6 Animal fats

Tropical oils (e.g. coconut, palm, cacao)Olive oil

Avocados

Peanuts & groundnuts

Tree nutsFlax

Fish oilMost seed oils (e.g. canola, safflower, sunflower)

Saturated fats contain no double bonds. Each carbon (C) has two hydrogens (H). The chain is “saturated” with hydrogens. Because of this chemical configuration, saturated fats are generally solid at room temperature.

Unsaturated fats, on the other hand, have one or more double bonds between the carbons. Thus not all of the carbons have hydrogens stuck to them. This puts a “kink” in the chain.

Monounsaturated fats have one double bond and polyunsaturated fats have more than one.

These molecular shapes of various fats are important, because the shapes determine how the various fats act in the body.

What is a “healthy fat”?

In popular terminology, the monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are what most people refer to as “healthy fats.”

Yet humans have likely consumed unprocessed forms of saturated fats (such as organ meats from wild game, blubber from seals and whales, milk, or coconuts) for their entire existence.

Humans evolved on diets consisting of marine life, wild game and/or inland plants, which provided abundant omega-3 and other unprocessed fats.

Early humans (and many hunter-gatherer groups today) consumed all parts of animals — including fatty tissues such as blubber, organs, and brains along with eggs from fish, fowl, and reptiles.

So, a better definition of “healthy fat” might be “relatively unprocessed fats from whole foods”.

Unhealthy fats are typically those that are industrially produced and designed to be nonperishable, such as:

- trans- fatty acids that appear in processed foods

- hydrogenated fats such as margarine (hydrogen is added to the fat chain to make a normally liquid and perishable fat into a solid and shelf-stable fat)

- most shelf-stable cooking oils (e.g. safflower, canola, corn oil, etc.)

Fats in balance

Since humans evolved by consuming a diet of whole foods, fat intake from mono-, poly-, and saturated sources was distributed evenly.

Scientists estimate that the omega-6/omega-3 ratio in a hunter-gatherer diet is around 1:1. Humans currently consume a ratio of about 16:1 to even 20:1 – an intake that’s way out of balance.

Much of our omega-6 and saturated fat intake is from refined fat sources, not from whole foods.

Items like corn oil, safflower oil, and factory-farmed meat/eggs/dairy contain unhealthy balances of fat. Soybean oil alone accounts for over 75% of oils consumed by Americans.

Why are healthy fats so important?

People are often concerned about excess dietary fat, but not getting enough “good” fats may also cause health problems.

A wide range of health effects

Fats exert powerful effects within the body.

We need adequate fat to support metabolism, cell signaling, the health of various body tissues, immunity, hormone production, and the absorption of many nutrients (such as vitamins A and D).

Having enough fat will also help keep you feeling full between meals.

Healthy fats have been shown to offer the following benefits.

Strong evidence

Average evidence

- Cardiovascular protection (though there is less evidence for protecting against heart failure)

- Improve body composition

- Alleviate depression

- Prevent cancers

- Preserve memory

- Preserve eye health

- Reduce incidence of aggressive behaviour

- Reduce ADHD and ADD symptoms

You’re a fathead… literally

Fat we consume is digested and either used for energy, stored in adipose (fat) tissue, or incorporated into other body tissues and organs.

Many of our body tissues are lipid (aka fat) based, including our brains and the fatty sheath that insulates our nervous systems. Our cell membranes are made of phospholipids, which means they’re fat-based too.

Thus, the fat we consume literally becomes part of our cells. It can powerfully influence how our cells communicate and interact.

For example, fat can affect signaling molecules that influence blood vessel constriction, inflammation, blood clotting, pain, airway constriction, etc. Since our brains are fat-based, changes in fat composition can affect transmission of nervous system impulses.

For this reason, balancing our fat intake can promote optimal functioning of our entire body. Therefore it’s important that we emphasize whole food fat sources in our diets, and supplement as necessary.

More on fat types

Omega-3s

The most important omega-3 fats are the following:

Our bodies mostly use DHA/EPA, and don’t convert ALA very well. Most plant-based sources (e.g. flax, hemp, and chia) are rich in ALA while marine animal sources (i.e. fish) and algae are rich in EPA and DHA.

- ALA (alpha-linolenic acid)

- DHA (docosahexaenoic acid)

- EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid)

Thus, blood levels of omega-3 fats are typically lower in plant-based eaters than in those who eat meat, so plant-based eaters should be particularly vigilant about proper fat intake.

ALA conversion is particularly poor in people who consume a typical Western diet. Thus, people who eat diets high in processed foods and refined carbohydrates, etc. will not reap many benefits from ALA.

Get your EPA/DHA from marine sources. (See AA Algae for more on plant-based sources.)

Monounsaturated fats

Monounsaturated fats (e.g. from nuts, seeds, olives, and avocados) appear to lower LDL cholesterol (aka the “bad” cholesterol). They may also increase HDL cholesterol (aka the “good” cholesterol), but evidence for this is not as clear.

CLA

Once everything is in order with your nutrition and lifestyle, consuming CLA (conjugated linoleic acid) might be another option.

CLA resembles LA (linoleic acid) but the structure is slightly different, giving it a different effect in the body. It may help to control levels of body fat.

Food sources of CLA include pasture-raised/grass-fed animals/eggs. Plant-based CLA supplements are usually derived from sunflower oil.

Saturated fat

Saturated fat seems to support the enhancement of good cholesterol.

Fats from palm oil and coconut oil are highly saturated. Palm and coconut also contain medium chain fats, which can support health and optimal body composition.

Due to the high prevalence of animal foods and tropical oils (from processed foods) and the low prevalence of whole plant foods in the modern diet, people tend to get too much saturated fat relative to unsaturated fat, and combine these saturated fats with refined carbohydrates. Health suffers as a result.

In addition, tropical oils (e.g. palm and coconut oils) usually appear as industrially refined, hydrogenated fats in processed foods, rather than in their native form.

If you choose to consume these tropical oils, make sure they are unrefined (e.g. whole coconut or extra-virgin, cold-pressed coconut oil). For healthy saturated fats, look for pasture-raised meat and dairy.

Summary and recommendations

Get a mix of fat types from whole, unprocessed, high-quality foods. These include nuts, seeds (hemp, flax, and chia are especially nutritious), fish, seaweed, pasture-raised/grass-fed animals/eggs, olives, avocado, coconut, and cacao nibs.

Avoid industrially processed, artificially created, and factory farmed foods, which contain unhealthy fats.

Keep it simple. Don’t worry too much about exact percentages and grams.

Supplement with algae oil or fish oil daily. We recommend 1-2 g of algae oil or about 3-6 g of fish oil each day.

A few safety notes

If you:

then check with your doctor and/or pharmacist before supplementing with additional omega-3s. However, it’s still generally safe for you to eat fish and seafood.

- are taking blood thinners;

- have heart rhythm disturbances;

- are scheduled for surgery in the immediate future; and/or

- have any bleeding disorders

Further Resources

Eat, move, and live… better.

Yep, we know…the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be. Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report. In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies – unique and personal – for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

He K, et al. Accumulated evidence on fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circulation 2004:109;2705-2711.

Lankinen M, et al. Fatty fish intake decreases lipids related to inflammation and insulin signaling – a lipidomics approach. PLoS One 2009;4:e5258. Epub Apr 23 2009.

Marchioli R, et al. Early protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: Time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-Prevenzione. Circulation 2002:105;1897-1903.

Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharacother 2002;56:365-379.

Whigham LD, et al. Efficacy of conjugated linoleic acid for reducing fat mass: a meta-analysis in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1203-1211.

Blankson H, et al. Conjugated linoleic acid reduces body fat mass in overweight and obese humans. J Nutr 2000;130:2943-2948.

Freund-Levi Y, et al. n-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study: a randomized double-blind trial. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1402-1408.

Morris MC. Docosahexaenoic acid and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1527-1528.

Schaefer EJ, et al. Plasma phosphatidylcholine docosahexaenoic acid content and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: the Framingham heart study. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1545-1550.

Norat T, et al. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:906-916.

Augustsson K, et al. A prospective study of intake of fish and marine fatty acids and prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:64-67.

Nemets B, et al. Addition of omega-3 fatty acid to maintenance medication treatment for recurrent unipolar depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:477-479.

Su KP, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder. A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2003;13:267-271.

Peet M & Horrobin DF. Dose-ranging study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with ongoing depression despite apparently adequate treatment with standard drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:913-919.

Davis BC & Kris-Etherton PM. Achieving optimal essential fatty acid status in vegetarians: current knowledge and practical implications. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78 (suppl):640S-646S.

Rosell MS, et al. Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in plasma in British meat-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:327-334.

Kris-Etherton PM, et al. AHA Scientific Statement. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2002;106:2747-2757.

Rotstein NP, et al. Protective effect of docosahexaenoic acid on oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of retina photoreceptors. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:2252-2259.

Xi ZP & Wang JY. Effect of dietary n-3 fatty acids on the composition of long-and very-long-chain polyenoic fatty acid in rat retina. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2003;49:210-213.

Wheaton DH, et al. Biological safety assessment of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in a randomized clinical trial for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Opthalmol 2003;121:1269-1278.

MacDonald IM, et al. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on retinal function in a patient with autosomal dominant Stargardt-like retinal dystrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:305-306.

Lombardo YB & Chicco AG. Effects of dietary polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids on dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance in rodents and humans. A review. J Nutr Biochem 2006;17:1-13.

Geelen A, et al. Fish consumption, n-3 fatty acids, and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1116=1125.

Raff M, et al. Conjugated linoleic acids reduce body fat in healthy postmenopausal women. J Nutr 2009;139:1347-52. Epub 2009 Jun 3.

Taubes G. Good Calories, Bad Calories. 2007. Knopf.

German JB & Dillard CJ. Saturated fats: what dietary intake? Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:550-559.

Volek JS & Forsythe CE. The case for not restricting saturated fat on a low carbohydrate diet. Nutrition & Metabolism 2005;2:21-23.

Dijkstra SC, et al. Intake of very long chain n-3 fatty acids from fish and the incidence of heart failure: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:922-928.

Danaei G, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: Comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Medicine 2009;6.

Phillips SA, et al. Benefit of low-fat over low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial health in obesity. Hypertension 2008;51:376.

Mozaffarian D, et al. Health effects of trans-fatty acids: experimental and observational evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63 Suppl 2:S5-S21.

Das UN. Essential fatty acids and their metabolites could function as endogenous HMG-CoA reductase and ACE enzyme inhibitors, anti-arrhythmic, anti-hypertensive, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, and cardioprotective molecules. Lipids Health Dis 2008;7:37.

Wallinga, David and Mark Muller. Considering the Contribution of US Agricultural Policy to the Obesity Epidemic: Overview and Opportunities. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition January 2009;4(1):3 – 19.

Surette, Marc E. The science behind dietary omega-3 fatty acids CMAJ. 2008 January 15; 178(2): 177–180. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071356.

No comments:

Post a Comment